Dada (/ˈdɑːdɑː/) or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century. The beginnings of Dada correspond to the outbreak of World War I. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war. Dada, in addition to being anti-war, had political affinities with the radical left and was also anti-bourgeois.

The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestos, art theory, theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works.

To quote Dona Budd’s The Language of Art Knowledge,

Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of the First World War. This international movement was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara’s and Marcel Janco’s frequent use of the words “da, da,” meaning “yes, yes” in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name “Dada” came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French-German dictionary happened to point to ‘dada’, a French word for ‘hobbyhorse’.

Origins and influences

The roots of Dada lay in pre-war avant-garde. Cubism and the development of collage, combined with Wassily Kandinsky’s theoretical writings and abstraction, detached the movement from the constraints of reality and convention. At least two works qualified as pre-Dadaist, a posteriori, had already sensitized the public and artists alike: Ubu Roi (1896) by Alfred Jarry, and the balletParade (1916–17) by Erik Satie. The influence of French poets and the writings of German Expressionists liberated Dada from the tight correlation between words and meaning, The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 when he created his first readymades (everyday objects found or purchased and declared art) such as a bottle rack).

Dada in Zurich, Switzerland, began in 1916, spreading to Berlin shortly thereafter, but the height of New York Dada was the year before, in 1915. Key figures in the movement included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch,Johannes Baader, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Richard Huelsenbeck, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters,Hans Richter, and Max Ernst, among others.

The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau Réalisme, pop art and Fluxus.

Political underpinnings

Many Dadaists believed that the ‘reason’ and ‘logic’ of bourgeoisie capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality. For example,George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest “against this world of mutual destruction.”

According to Hans Richter Dada was not art: it was “anti-art.” Dada represented the opposite of everything which art stood for. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend.

As Hugo Ball expressed it, “For us, art is not an end in itself … but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.”

Art techniques developed

Dada activities included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media.

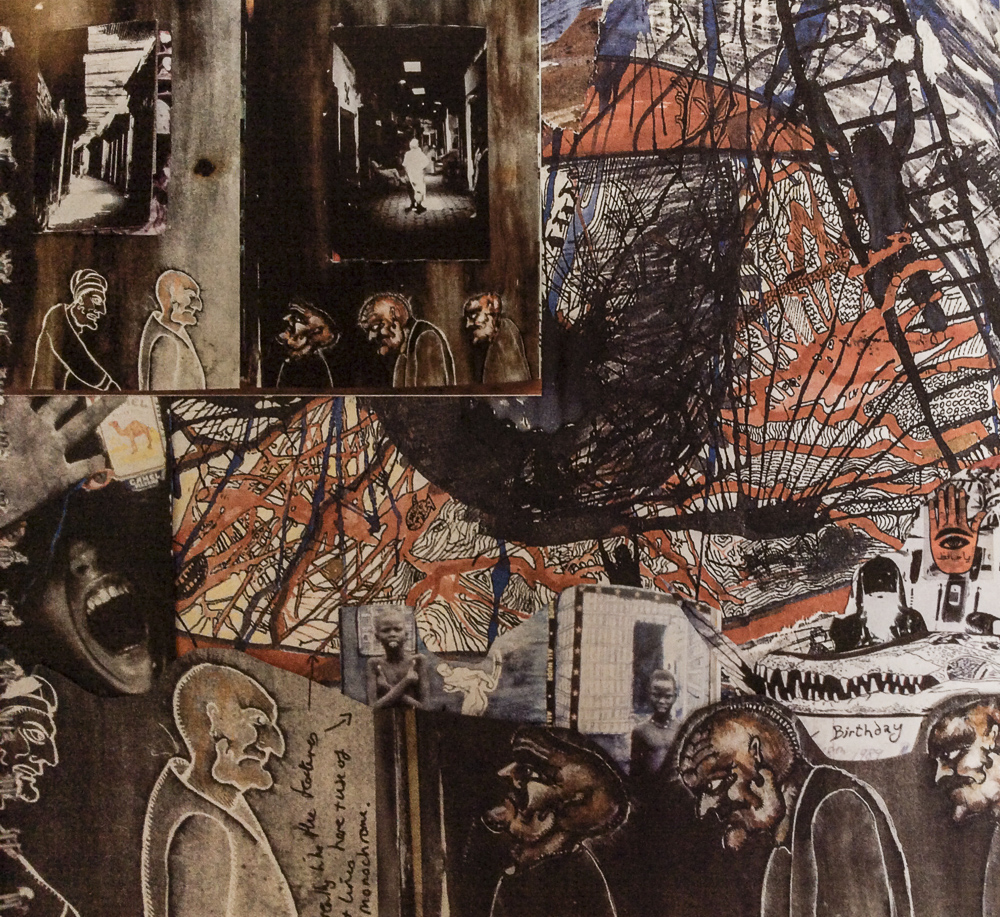

Collage

The Dadaists imitated the techniques developed during the cubist movement through the pasting of cut pieces of paper items, but extended their art to encompass items such as transportation tickets, maps, plastic wrappers, etc. to portray aspects of life, rather than representing objects viewed as still life.

Photomontage

The Dadaists – the “monteurs” (mechanics) – used scissors and glue rather than paintbrushes and paints to express their views of modern life through images presented by the media. A variation on the collage technique, photomontage utilized actual or reproductions of real photographs printed in the press. In Cologne, Max Ernst used images from the First World War to illustrate messages of the destruction of war.

Assemblage

The assemblages were three-dimensional variations of the collage – the assembly of everyday objects to produce meaningful or meaningless (relative to the war) pieces of work including war objects and trash. Objects were nailed, screwed or fastened together in different fashions. Assemblages could be seen in the round or could be hung on a wall.[31]

Readymades

Marcel Duchamp began to view the manufactured objects of his collection as objects of art, which he called “readymades”. He would add signatures and titles to some, converting them into artwork that he called “readymade aided” or “rectified readymades”. Duchamp wrote: “One important characteristic was the short sentence which I occasionally inscribed on the ‘readymade.’ That sentence, instead of describing the object like a title, was meant to carry the mind of the spectator towards other regions more verbal. Sometimes I would add a graphic detail of presentation which in order to satisfy my craving for alliterations, would be called ‘readymade aided.’” One such example of Duchamp’s readymade works is the urinal that was turned onto its back, signed “R. Mutt”, titled “Fountain”, and submitted to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition that year. The piece was not displayed during the show, a fact that unmasked the inherently biased system that was the art establishment, seeing as any artist that paid the entry fee could in theory display their art, but the work of R. Mutt was banished by the judgment of a group of artists.

Poetry; music and sound

Dada was not confined to the visual and literary arts; its influence reached into sound and music. Kurt Schwitters developed what he called sound poems, while Francis Picabia and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes composed Dada music performed at the Festival Dada in Paris on 26 May 1920. Other composers such as Erwin Schulhoff, Hans Heusser and Albert Savinio all wroteDada music, while members of Les Six collaborated with members of the Dada movement and had their works performed at Dada gatherings. Erik Satie also dabbled with Dadaist ideas during his career, although he is primarily associated with musical Impressionism.

In the very first Dada publication, Hugo Ball describes a “balalaika orchestra playing delightful folk-songs.” African music and jazz was common at Dada gatherings, signaling a return to nature and naive primitivism.

Artists

- Louis Aragon (1897-1982), France

- Jean Arp (1886-1966), Germany, France

- Hugo Ball (1886-1927), Germany, Switzerland

- André Breton (1896-1966), France

- Otto Dix (1891-1969), Germany

- Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) Netherlands

- Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), France

- Paul Éluard (1895-1952), France

- Max Ernst (1891-1976), Germany, USA

- Julius Evola (1898-1974), Italy

- George Grosz (1893-1959), Germany, France, USA

- Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971), Germany

- John Heartfield (1891-1968), Germany, USSR, Czechoslovakia, Great Britain

- Hannah Höch (1889-1978), Germany

- Richard Huelsenbeck (1892-1974), Germany

- Marcel Janco (1895-1984), Romania, Israel

- Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927), Germany, USA

- Clément Pansaers (1885-1922), Belgium

- Francis Picabia (1879-1953), France

- Man Ray (1890-1976), France, USA

- Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1884-1974), France

- Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), Germany

- Walter Serner (1889-1942), Austria

- Philippe Soupault (1897-1990), France

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943), Switzerland, France

- Tristan Tzara (1896-1963), Romania, France

- Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), USA