Billingham was born in Birmingham in 1970 and studied as a painter at Bournville College of Art and the University of Sunderland. He came to prominence through his candid photography of his family in Cradley Heath, a body of work later added to and published in the acclaimed book Ray’s A Laugh (1996).

Ray’s a Laugh documents the life of his alcoholic father Ray, and obese, heavily-tattooed mother, Liz. It is a portrayal of the poverty and deprivation in which he grew up in Thatcher’s Britain. Billgham used a cheap low quality film and shot the images without caring about the composition; the result is a family portait stuffy and unconventional, characterised by a kind of lucidity which suggests both intellectual detachment and emotional closeness.The brash colours and bad focus which adds to the authenticity and frankness of the series.

I have not used any digital cameras as I still find them very difficult to use. They make me look at things with a different kind of attention I think. Digital cameras always have a screen on the back of them nowadays that enables you to see your photograph as soon as you’ve taken it and that distracts me. I end up looking at the picture I’ve just taken and trying to better it. And as soon as I start doing that, the ‘moment’ is lost.

He wasn’t initially concerned about photography when he was living with his father Ray. He was simply a would-be painter in need of a patient model:

“I was living in this tower block; there was just me and him. He was an alcoholic, he would lie in the bed, drink, get to sleep, wake up, get to sleep, didn’t know if it was day or night. But it was difficult to get him to stay still for more than say 20 minutes at a time so I thought that if I could take photographs of him that would act as source material for these paintings and then I could make more detailed paintings later on. So that’s how I first started taking photographs.”

“My dad had moved into my mum’s place by this time and I could not believe how it looked. She’d had two years away from my dad so she had created her own psychological space around herself that was very ‘carnivalesque’ and decorative. There were dolls, jigsaws everywhere. She’d got load of pets by this time; she had about ten cats … two, three dogs.”

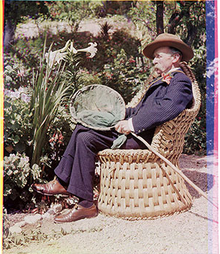

It has been called ‘an honest portrait’, partly depressing and partly funny, of the photographer’s family, composed by Ray, the alcoholic and unemployed father, Liz, the obese and heavy smoking mother, by the brother Jason and several pets. Ray, his father, and his mother Liz, appear at first glance as grotesque figures, with the alcoholic father drunk on his home brew, and the mother, an obese chain smoker with an apparent fascination for nicknacks and jigsaw puzzles.They all share the same messy and crowded apartment and are struck during their daily routine, almost unaware that someone is photographing them. The thing that makes Billingham’s work diferent is the total lack of barriers towards the audience: the subjects are photographed while eating on the couch, while playing with pets, while making a jigsaw puzzle, but also in some occasions that usually remain private: for example while lying in bed or passed out on the bathroom floor for having drunk too much.

However, there is such integrity in this work that Ray and Liz ultimately shine through as troubled yet deeply human and touching personalities.

Billingham’s work was included in the exhibition Sensation at the Royal Academy of Art which showcased the art collection of Charles Saatchi and included many of the Young British Artists.] Also in 1997, Billingham won the Citigroup Photography Prize. He was shortlisted for the 2001 Turner Prize, for his solo show at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham.

He has also made landscape photographs at places of personal significance around the Black Country, and more of these were commissioned in 2003 by the arts organisation The Public, resulting in a book. He has also experimented with video films and video projections.

In late 2006, Billingham exhibited a major new series of photographs and videos inspired by his memories of visiting Dudley Zoo as a child. The series, entitled “Zoo”, was commissioned by Birmingham-based arts organisation, VIVID and was exhibited at Compton Verney Art Gallery in Warwickshire.

In the following year he created a series of photographs of “Constable Country”, the area on the Essex / Suffolk border painted by John Constable. These were exhibited at the Town Hall Galleries, Ipswich. In 2009-2010, Billingham participated in a collective exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany titled: Ich, zweifellos.

He now lives near Swansea, and travels widely. He is a lecturer in Fine Art Photography at the University of Gloucestershire and a third year tutor at Middlesex University (2012).