Jan Tschichold (1902- 1974) was a typographer, book designer, teacher and writer.

Modernism: Die neue Typographie

Tschichold became a convert to Modernist design principles in 1923 after visiting the first Weimar Bauhaus exhibition. He wrote an influential 1925 magazine supplement; then had a 1927 personal exhibition. The book ‘Die Neue Typographie’ was a manifesto of his theories of modern design and codified many other Modernist design rules:

- importance of machine composition

- use of standardised paper sizes for all printed matter

- effective use of sans serif (Grotesque) typefaces using different sizes and weights of type in order to quickly and easily convey information.

- non-centred design and asymmetrical placing of contrasting elements with flush left headlines of irregular lengths

- layouts based on horizontal and vertical underlying grids with spatial interval and empty spaces employed as design components.

He advocated the Van de Graaf canon based on proportions in medieval manuscripts and based on Golden Section used in book design to divide a page in pleasing proportions.

This book was followed with a series of practical manuals on the principles of Modernist typography which had a wide influence among ordinary workers and printers in Germany.

Return to Classicism

Tschichold slowly abandoned his rigid beliefs from around 1932 onwards (e.g. his Saskia typeface of 1932, and his acceptance of classical Roman typefaces for body-type) as he moved back towards Classicism in print design. He later condemned Die neue Typographie as too extreme. He also went so far as to condemn Modernist design in general as being authoritarian and inherently fascistic. He now advocated:

- symmetrical typographic treatments as more appropriate for great works of literature.

- classical typefaces like Garamond, Janson, Baskerville and Bell because of legibility

- importance of grids underlying layout design.

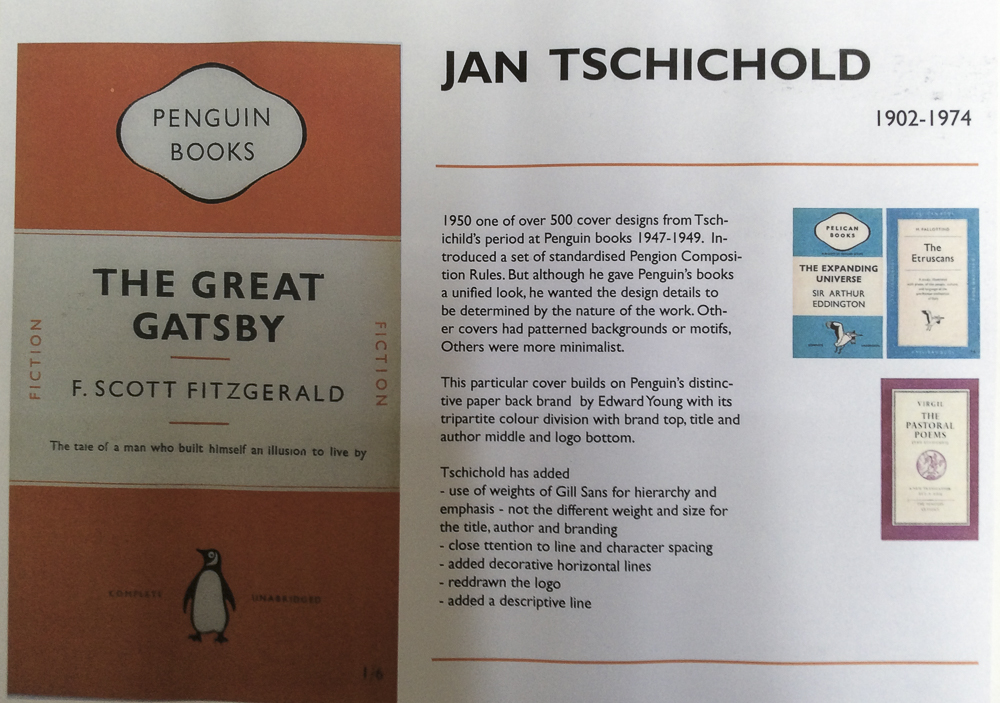

Penguin Books

Between 1947–1949 Tschichold lived in England where he oversaw the redesign of 500 paperbacks published by Penguin Books, leaving them with a standardized set of typographic rules, the Penguin Composition Rules. Although he gave Penguin’s books (particularly the Pelican range) a unified look and enforced many of the typographic practices that are taken for granted today, he allowed the nature of each work to dictate its look, with varied covers and title pages. In working for a firm that made cheap mass-market paperbacks, he was following a line of work—in cheap popular culture forms (e.g. film posters)—that he had always pursued during his career.

Typefaces

His abandonment of Modernist principles meant that, even though he was living in Switzerland after the war, he was not at the centre of the post-war Swiss International Typographic Style. Unimpressed by the use of realist or neo-grotesque typefaces, which he saw as a revival of poorly-designed models, his survey of typefaces in advertising deliberately made no mention of such designs, save for a reference to ‘survivals from the nineteenth-century which have recently enjoyed a short-lived popularity.’

Sabon typeface 1967 is the best known.

Between 1926 and 1929, he designed a “universal alphabet” to clean up the few multigraphs and non-phonetic spellings in the German language. For example, he devised brand new characters to replace the multigraphs ch and sch. His intentions were to change the spelling by systematically replacing eu with oi, w with v, and z with ts. Long vowels were indicated by a macron below them, though the umlaut was still above. The alphabet was presented in one typeface, which was sans-serif and without capital letters.

Other typefaces: Transit (1931), Saskia (1931/1932) and Zeus (1931).

Biography

(edited from Wikipedia)

Tschichold was the son of a provincial signwriter, and unlike most other typographers of his time, was trained in calligraphy. This may help explain why he never worked with handmade papers and custom fonts as many typographers did, preferring instead to use stock fonts on a careful choice from commercial paper stocks.

After the election of Hitler in Germany, all designers had to register with the Ministry of Culture, and all teaching posts were threatened for anyone who was sympathetic to communism. Soon after Tschichold had taken up a teaching post in Munich at the behest of Paul Renner, they both were denounced as “cultural Bolshevists”. Ten days after the Nazis surged to power in March 1933, Tschichold and his wife were arrested. During the arrest, Soviet posters were found in his flat, casting him under suspicion of collaboration with communists. All copies of Tschichold’s books were seized by the Gestapo “for the protection of the German people”. After six weeks a policeman somehow found him tickets for Switzerland, and he and his family managed to escape Nazi Germany in August 1933.

Apart from two longer stays in England in 1937 (at the invitation of the Penrose Annual), and 1947–1949 (at the invitation of Ruari McLean, the British typographer, with whom he worked on the design of Penguin Books), Tschichold lived in Switzerland for the rest of his life. Jan Tschichold died in the hospital at Locarno in 1974.